While BMC and Mumbaikars obsess over lake levels every monsoon, the truth is that despite overflowing reservoirs, the city still doesn’t have enough water in an enormously skewed demand and supply chain

Mumbai’s lakes are brimming. Even the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) last week confirmed that there would be no water cuts, as the lakes were 99.23 per cent full as of September 30, which signals the end of monsoon.

Despite this good news, the experiences of the last few years reveal another picture. While data from the last four years show that the lakes were filled up by the end of the monsoon season, the city is reported to have faced water cuts during three out of those four years. This only goes to show that the city’s water supply network is still lagging behind.

Some areas in the city appear to be the biggest sufferers. Take Charkop, a locality in the Western suburb, for instance. Once home to several chawls, the unplanned gentrification of the neighbourhood in the last 40 years, has put tremendous pressure on existing resources.

ALSO READ

Horoscope today, October 9: Check astrological predictions for all zodiac signs

Maharashtra hospital deaths: Sena (UBT), Cong demand state cabinet’s resignation

Mumbai: Alert BEST bus conductor prevents accident as driver falls unconscious

Thane: One dead, one injured after fatal accident at Cadbury Junction

Palghar school initiates probe into ragging complaints involving 5 students

The rainwater that is harvested lasts for four to five months for non-potable use like washing cars

The chawls have now made way for ground plus one and two-storey structures. Even the older buildings have been torn down, and been replaced with towers. “The population and need of water per house have increased tremendously. But the pipelines are of the same size and are corroded. So, we face water shortage almost every day,” said Dr Shankar Jamsandekar, a resident of Charkop.

In Koldongri, Andheri, the residents in August had complained about water pressure reducing, even though the BMC claimed that there wasn’t any cut. Newer buildings in the western suburbs are currently meeting part of their water needs through borewells. “We have a borewell in our newly built society. The network supplies water to toilets, while water from the corporation is used for our kitchens and bathrooms,” said Nilesh Jadhav, a resident of Borivli West.

The state government had made rainwater harvesting mandatory for all buildings over 1,000 square metres in 2002, but its implementation has remained only on paper. BMC’s Rainwater Harvesting Cell remains inactive and the corporation doesn’t have data of buildings that have the system. The BMC also does not have data on housing societies whose builders received permission to construct their project, on condition that they’d have a sewage water treatment plants (STP) and reuse the treated water.

Also read: Mumbai: Water supply to remain affected in following areas on October 9 and 13

But a few complexes like Godrej Prime in Sahakar Nagar, Kurla, have rainwater harvesting as well as STP. “We have a one lakh litre underground tank for rainwater and the water lasts for four to five months for non-potable use like washing cars,” said Dr Vijay Sangole, a member of the committee of Godrej Prime. The STP was built by the developer and it generated 80,000 litres of water per day, which the complexes use for their toilets. “But our requirement is half of it and we are ready to provide the remaining treated water to others, so that we can recover the maintenance cost of the plant,” Sangole added. Maintenance of the plant costs about Rs 70,000-Rs 80,000.

(From left) Committee members Shrikant Gupta, Milind Khanolkar, Pravin Mendon and Dr Vijay Sangole point to the rainwater harvesting pipes

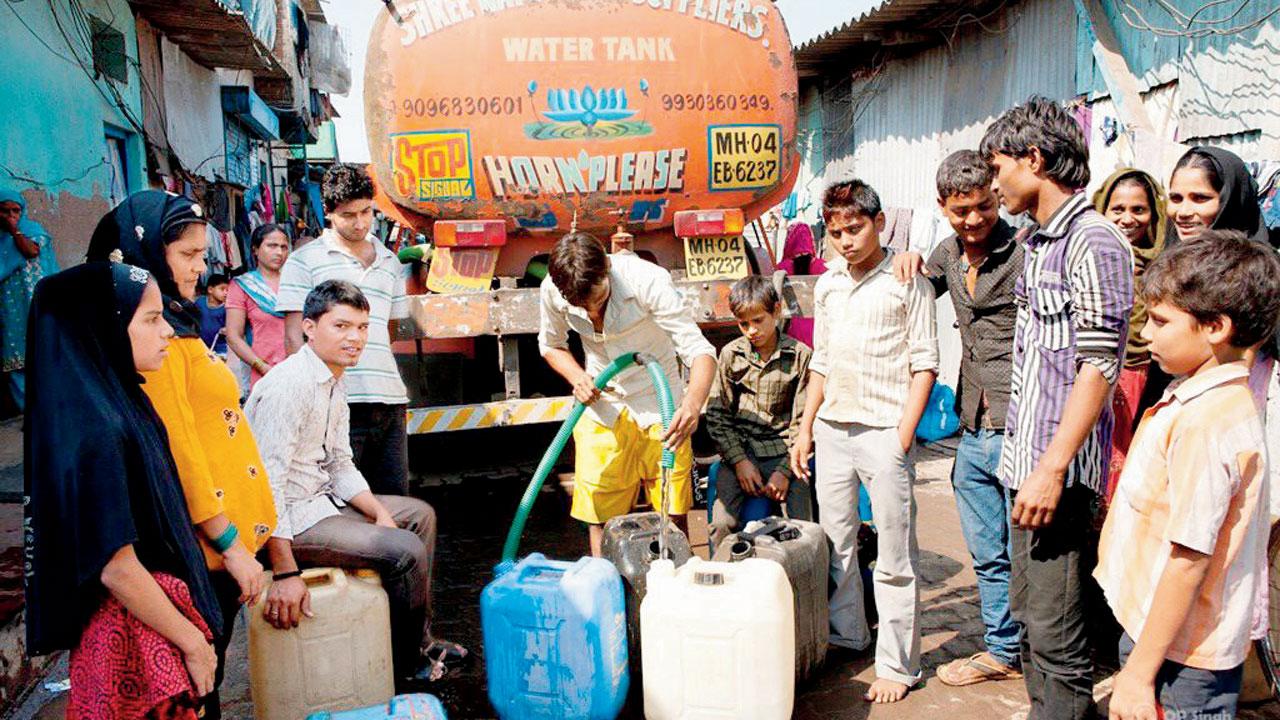

There are also tankers that supply non-potable water to construction sites. Rajesh Thakur, secretary of the Mumbai Water Tanker Association (MWTA), the apex body of operators supplying potable and non-potable water, said, “We provide an average of 50 million litres of non-potable water from wells, mainly for construction sites. When the BMC imposes cuts or if the pipeline bursts, then the demand increases. We transport potable water to the societies or slums from civic pipelines itself.” But these measures are few and far between, as the water needs of the city are still not being met.

Need more water sources

Currently, seven lakes and dams are supplying water to the city. Vihar and Tulsi lakes are in the city, while other lakes Tansa, Modak Sagar, Middle Vaitarna, Upper Vaitarna and Bhatsa are in Palghar, Thane and Nashik respectively, and located at a distance of about 100 to 175 km from the city. The last lake constructed was Middle Vaitarna that started storing water in 2014. The water storage capacity of all seven lakes is 14.47 lakh million litres. The daily supply quantity to the city is 3,850 million litres per day (MLD) that remains the same for the last 10 years. The current need of the city has reached to 4,500 MLD.

The water tanks supply an average of 50 million litres non-potable water daily from wells, mainly for constructions sites

“The city is under construction and the number of homes is increasing by the day. The BMC provides water as per the national criteria—45 litres per capita per day (LPCD) for slums and 135 LPCD for residential buildings. But the need for water per person has increased due to washing machines, toilet flushes, car washing etc,” said Madhukar Kambale, former chief of the hydraulic department of the BMC.

Climate change has made the city more vulnerable. In the last few years, the rain pattern in the city has changed. Krishnanad Hosalikar, head of climate research and Services, and SI Division, IMD, said “We have studied the pattern of monsoon over the country. The monsoon comes on time and withdraws 10 to 15 days later on. But the rainfall does not spread uniformly. Most of the days remain dry with very heavy rain for a few days. This year, 90 per cent of the season’s rain was received only in July in Mumbai.”

The city’s water stock during the monsoon season determines the water cuts in the following year. Last year, on September 30, the city collected 14,26,509 million litres (98.56 per cent), due to which Mumbai faced a 10 per cent water cut from July 5 to August 9 this year as water stock went down to seven per cent. Similarly, in 2021, the city collected 14,29,542 (98.77 per cent), and witnessed a 10 per cent water cut from June 28 to July 12, 2022, as the water stock went down to nine per cent. Incidentally, in 2019, the city collected significantly better stock (14,33,405 or 99.04 per cent), but had a longer water cut period from August 5 to 29, 2020 due to poor rainfall that season. Several factors, hence, determine the city’s water needs.

Plan to increase stock afoot

As per the population growth trend, the projected population in 2041 is anticipated to reach 17.24 million. It would be almost 40 per cent more than 2011, and water demand would rise up to 5,940 million litres per day (MLD). To make up for the shortfall in demand and supply, the BMC had planned to construct dams. An officer from the BMC said, “The Gargai dam [440 MLD], Pinjal dam [865 MLD] and Damanganga-Pinjal River link project [1,586 MLD] are supposed to be completed in phases by 2040. On completion of these three projects, water storage capacity would have increased by 2,891 MLD.”

(From left) Rajesh Thakur, secretary and Jeetu Shah, vice-president of Mumbai Water Tanker Association (MWTA)

Gargai dam was expected to be completed by 2020, but they are yet to get permissions. It will affect over four lakh trees spread over 700 hectares of Tansa Wildlife sanctuary. “Recently, we received permission from the Ministry of Tribal Affairs and now, we are waiting for a response from the Ministry of Wildlife. All permissions and tender process may take another year and half. The construction of the dam will require another three years.” The estimated cost of the project is said to be around R3000 crore.

The other two projects—Damanganga and Pinjal—haven’t been taken up. “Construction of dams outside the city and carrying water through 150 km long tunnels are an expensive affair. Environmental issues are also a concern. The BMC is looking for other options like a desalination project or potable water through sewage treatment plants,” said another official from the water supply project department of the BMC. The desalination project has a capacity of 200 MLD (of converting seawater into potable water) that can be expanded to 400 MLD at a later stage. The project was estimated to cost Rs 3,500 crore in 2021, including maintenance of the plant for 20 years. The tender hasn’t been floated yet.

Nilesh Jadhav, Madhukar Kambale and Swapna Mhatre

Meanwhile, the BMC has undertaken a project worth Rs 27,000 crore for seven sewage treatment plants (STPs) in Worli, Bandra, Dharavi, Versova, Malad, Ghatkopar, and Bhandup to treat 2,464 million litres of sewage. The BMC recently appointed a consultant to study the feasibility of converting 12 million litres of effluent waste into potable water daily at Colaba plant. After studying its feasibility, the BMC will consider setting up a plant. “If it succeeds, we may get around 1,300 MLD of potable water that can be supplied from the regular network. In many parts of the world, the treated water is used for drinking. But the challenge is to change the mindset of people residing here,” said a BMC official. It will take at least another three years.

Why opt for costly solutions?

Swapna Mhatre, former corporator of Bandra said, leakages are the main issue for water shortage. “The BMC should replace all the old lines without waiting for complaints of bursting. It will save water and also ensure that citizens get uninterrupted water supply.”

Currently, around 25 per cent of the water, more than 1,000 MLD, has been labelled as non-revenue water (NRW). This includes water lost through leakages, thefts, unmetered connections etc. “If the city can bring it down to 15 per cent, which is the national norm, we can save 400 MLD, which is daily supply from one dam. The BMC should invest in the latest leak detection technologies,” said Madhukar Kambale, a retired BMC officer. “A water audit of buildings is also necessary to check for internal leakages like tap or toilet flush. Singapore has a stainless-steel pipeline network and the leakage is below 5 per cent,” he added. He feels that the BMC should create awareness to save water. “Saving water means creating stock for others,” he said.

Source : mid-day