At Chatterjee & Lal, Mortimer Chatterjee recreates two chapters out of the life of one of India’s greatest pedagogues and essayists and authors and poet KG Subramanyan who was known to his students and friends as Manida.

Tyeb Mehta and Manida

Split into two parts this exhibition is like a reverie doused in double dip nostalgia as well as the haunts of history and impeccable research. Mortimer Chatterjee who is one of India’s greatest silent curators, puts together a stellar unveiling of the multifaceted Manida both as an avid learner as well as a textile experimenter. In looking at the installation images one recalls Manida’s friend Tyeb Mehta who told me in an interview that conversations with Manida were distilled in the mosaic of the past and the present. Tyeb said that he didn’t know anyone in Santiniketan or Baroda who was as greatly respected as Manida. According to Tyeb respect for the guru, is part of our value systems, he valued Manida’s elegance and tenderness; and passion , integral ingredients in a value system, linked to our appreciation of the great masters. In a quaint way this exhibition is a reflection of the profundities of the vision and explorations of KG Subramanyan whose 100th birth centenary happens next year.

Trio of drawings

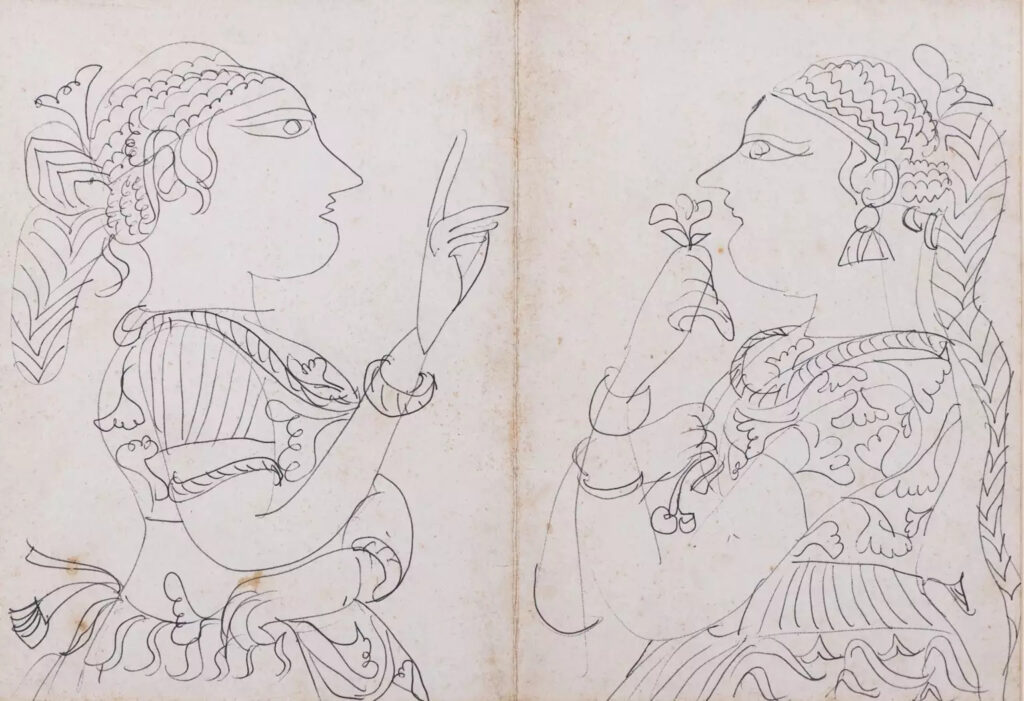

The first part of the exhibition is entitled His Art as Language. We look at Manida’s drawings, lithe and lean and full of evocations, telling us that artists must be interpreters of cultural epochs and traditions. We also look at an unravelling of facets unknown in terms of distinction and myriad practices. Mortimer affirms: “ We were keen to foreground Subramanyan’s relationship to design and how this impacted his wider artistic practice. In doing so, we were lucky enough to be able to represent very rare material which has never been displayed before.”

A trio of drawings are as much about feminine fervour as well as the richness of hybrid manifestations. The little threads of plantar varieties and the evocative emotions of the soliloquy of the women as subjects all come together to create a quilt of quixotic drama. Narratives were Manida’s strength, the panning out of his subjects from antiquity to modernist moorings all have such an enchanted aura born of his observations.

Wall Paintings and designs

The second section of works looks at his work at the Weaver’s Centre Mumbai. Ink on Paper was his forte, for the Weavers’ Service Centre, consisting of Madhya Pradesh Wall Paintings and Tattoo Design, 1958 are a monochromatic of medley. Economy of lines and the definite grasp of the figurative form from folk to indigenous idioms all create a lucid conversation of knowing the substrata of Indian art history.

The installation shot of Do Hands Have a Chance is at once a riveting ripple of the analogies of time and tide. The catalogue speaks of Subramanyan’s relationship with the Weavers Service Centre , which began with making textile designs in 1959. As a design thinker, he was an integral part of the efforts being made to revive Indian textile design. At the New York World Fair in 1965, Subramanyan used hemp fibres and discarded pieces of cloth to create a massive textile relief, stressing on the interdependence of art and craft in the Indian design vocabulary.

Weaver’s Centre Mumbai

For Chatterjee & Lal this exhibition is an insight of multiplicity and the truth that curating a master requires restraint and research born of selfless desires. The exhibition includes a selection of Subramanyan’s work with textiles, books and toys as it views his practice through a design-historical lens.

In 1958, the Weavers’ Service Centre opened at the Opera House—where, in its early stages, Subramanyan worked for one and half years. The exhibition includes newly discovered material comprising some of his designs done for the Centre.

History says in 1962, when he returned to teach at the MS University in Baroda, Subramanyan was instrumental in founding the Fine Arts Faculty’s annual fair, for which he designed the first of his toys, a prime example of his desire to collapse boundaries between activities that promoted working with one’s hands. It was also for the fairs that Subramanyan began to experiment with illustrations for books, often aimed at children, a facet of his practice that would reveal itself more forcefully in the decades to come.

Source : The Times of India